Myocardial Infarction Health care Atlas for Norway

The Health care Atlas for myocardial infarction contains two parts: 1) an update of results from the Elderly Health Atlas with admissions for myocardial infarction and revascularization, and 2) rehabilitation after myocardial infarction.

Rehabilitation in specialist health services is examined in two ways: 1) activity registered with rehabilitation codes; here called standard rehabilitation, and 2) standard rehabilitation plus activity registered as learning and mastery courses and/or training.

The analyses are based on data from the Norwegian Patient Register and Norwegian Registry for Primary Health Care (KPR) for the period 2018-2022.

Main Findings

Main Findings

- In the period 2018-2022, only 14% of patients received standard rehabilitation after an acute myocardial infarction in Norway, despite well-documented effects of cardiac rehabilitation.

- Approximately one out of every four patients received standard rehabilitation, learning and mastery courses (LMC), or training in specialist health services after an acute myocardial infarction. The percentage receiving rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction was significantly lower for patients aged 65 and older.·

- There was significant and unwarranted geographical variation in the use of rehabilitation after myocardial infarction. . For those who received rehabilitation, the extent, content, organization, and time after the infarction when rehabilitation started varied.

- The number of elderly (75 years and older) admitted with acute myocardial infarction has decreased, despite an increase in the elderly population.

- There was little geographical variation in the number of patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction per 1,000 population, excluding the areas with the highest and lowest rates.·

- There was moderate geographical variation in revascularization rates for the elderly (75 years and older), and little variation for the general population (18 years and older).

- As in 2013-2015, there was no correlation between admission for acute myocardial infarction and revascularization of the heart for the elderly (75 years and older). For all adults (18 years and older), the correlation was moderate. There were greater geographical variations in treatment practices for the elderly than for all adults combined.

Assessment of variation in rehabilitation

| Type of rehabilitation | Number | Percentage | Lowest percentage | Highest percentage | EQ | EQ2 | EQ3 | CV | SCV | SCV2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard rehabilitation | 1 315 | 14% | 2% | 41% | 20.5 | 9.3 | 6.3 | 88.0 | 67.1 | 45.0 |

| Total rehabilitation | 2 444 | 26% | 9% | 46% | 5.1 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 41.1 | 29.5 | 23.4 |

| Training with physioterapist | 1 635 | 4% | 2% | 13% | 6.5 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 62.1 | 18.4 | 13.8 |

To determine whether the variation in the use of services is undesirable/unjustified, we compared the use of health services with the prevalence of myocardial infarction. Larger discrepancies between prevalence and use of health services indicate unjustified variation.

About the Measures of Variation The Extremal Quotient is simple measure of variation. The EQ shows the ratio between the highest and lowest rate, while EQ2 shows the ratio between the second highest and second lowest rate. Higher EQ values therefore indicate greater variation in the rates. The coefficient of variation (CV) takes all the rates into account and is thus a more comprehensive measure of variation. The coefficient of variation is the standard deviation of the rates, divided by the mean of the rates, multiplied by 100. The systematic component of variation (SCV) highlights systematic variation and is therefore considered the most decisive measure of variation. Technically, SCV represents total variation minus random variation between areas. For SCV2, the highest and lowest values are excluded, which makes the measure less sensitive to extreme values. It has been suggested that SCV values greater than 3 are likely to be largely due to differences in practice within the healthcare service. We define the magnitude of variation as follows:

- SCV less than 3 indicates low variation,

- SCV between 3.1–5.4 indicates moderate variation,

- SCV between 5.5–10.0 indicates high variation, and

- SCV greater than 10.0 indicates extremely high variation.

Assessment of variation in rates

| Indicator | Number | Rate per 1 000 | Lowest rate | Highest rate | EQ | EQ2 | EQ3 | CV | SCV | SCV2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction, admitted patients, 18 years and above | 11 846 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 17.2 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Myocardial infarction, admitted patients, 75 years and above | 5 223 | 12.8 | 8.9 | 17.4 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 17.7 | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| Revascularization, 18 years and above | 13 038 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 18.6 | 3.3 | 1.9 |

| Revascularization, 75 years and above | 3 787 | 9.3 | 6.8 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 22.6 | 5.0 | 3.8 |

To determine whether the variation in the use of services is undesirable/unjustified, we compared the use of health services with the prevalence of myocardial infarction. Larger discrepancies between prevalence and use of health services indicate unjustified variation.

About the Measures of Variation The Extremal Quotient is simple measure of variation. The EQ shows the ratio between the highest and lowest rate, while EQ2 shows the ratio between the second highest and second lowest rate. Higher EQ values therefore indicate greater variation in the rates. The coefficient of variation (CV) takes all the rates into account and is thus a more comprehensive measure of variation. The coefficient of variation is the standard deviation of the rates, divided by the mean of the rates, multiplied by 100. The systematic component of variation (SCV) highlights systematic variation and is therefore considered the most decisive measure of variation. Technically, SCV represents total variation minus random variation between areas. For SCV2, the highest and lowest values are excluded, which makes the measure less sensitive to extreme values. It has been suggested that SCV values greater than 3 are likely to be largely due to differences in practice within the healthcare service. We define the magnitude of variation as follows:

- SCV less than 3 indicates low variation,

- SCV between 3.1–5.4 indicates moderate variation,

- SCV between 5.5–10.0 indicates high variation, and

- SCV greater than 10.0 indicates extremely high variation.

A myocardial infarction occurs when the blood supply to parts of the heart is blocked, causing damage to the heart muscle. A myocardial infarction is a serious condition that develops quickly. It is therefore important to start treatment early.

Each year, just under 11,000 Norwegians suffer from an acute myocardial infarction, with an annual decrease of about 3% since 2015 (Annual Report 2022, Norwegian Myocardial infarction Register). In about 25% of patients, one of the coronary arteries is completely blocked, often due to a rupture in the surface of a narrow part of the blood vessel and the formation of a thrombus (blood clot). In the remaining 75% of myocardial infarction, there are minor ECG changes, and the coronary artery is usually not completely blocked.

In Norway, there are no specific guidelines for rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction, and the European guidelines are followed (Ambrosetti et al. 2020 and Visseren et al. 2021), as well as the National Professional Guideline for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease (Norwegian Directorate of Health).

Patients with Myocardial Infarction

Main Findings:·

- The number of elderly admitted with acute myocardial infarction has decreased, despite an increase in the elderly population.

- The admission rate for myocardial infarction was highest in the Finnmark catchment area. This indicates that the prevalence of myocardial infarction is higher in Finnmark than in the rest of the country.

- The geographical variation in admissions for myocardial infarction was small when excluding the referral areas with the highest (Finnmark) and lowest rates (Diakonhjemmet area/Oslo West).

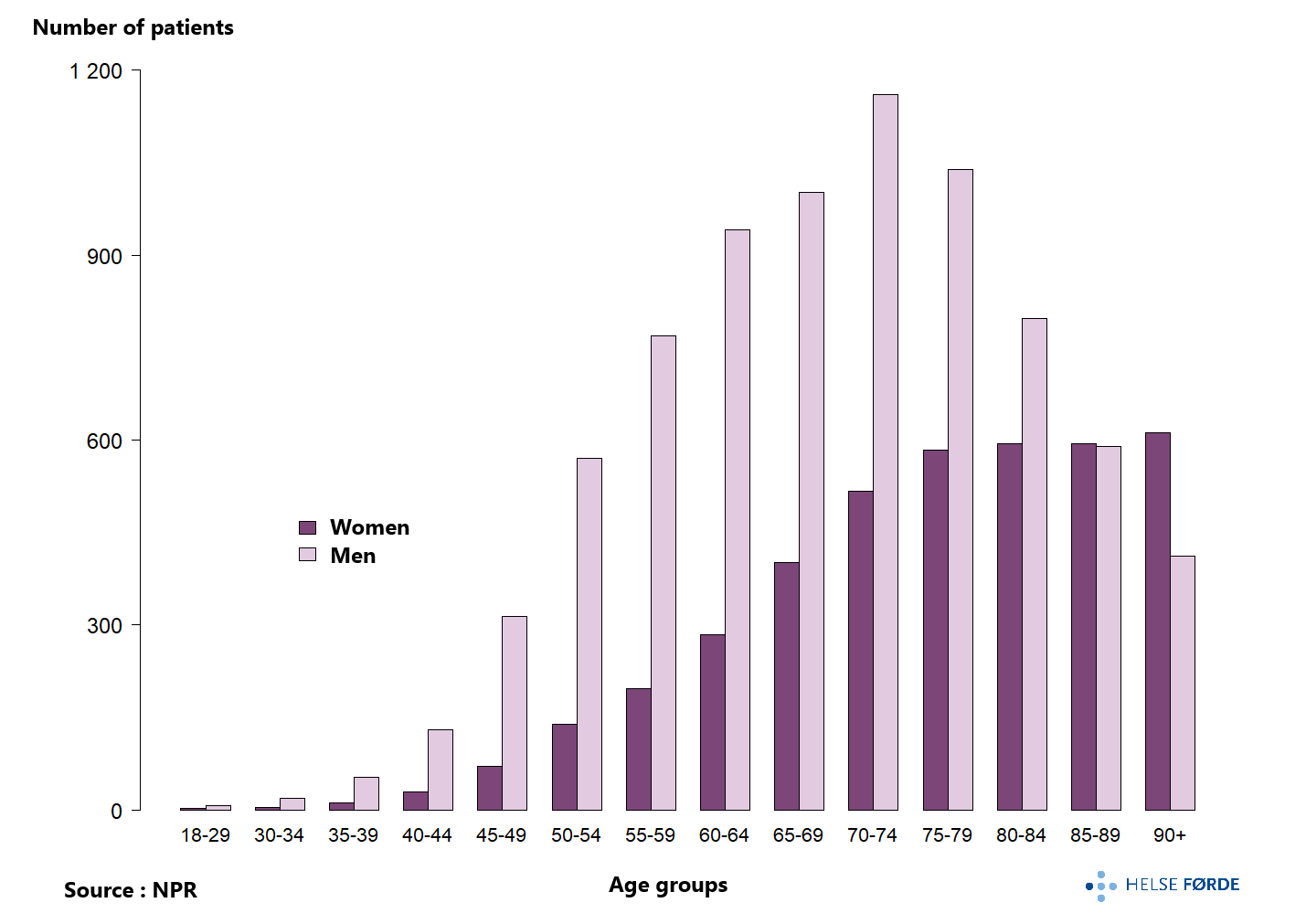

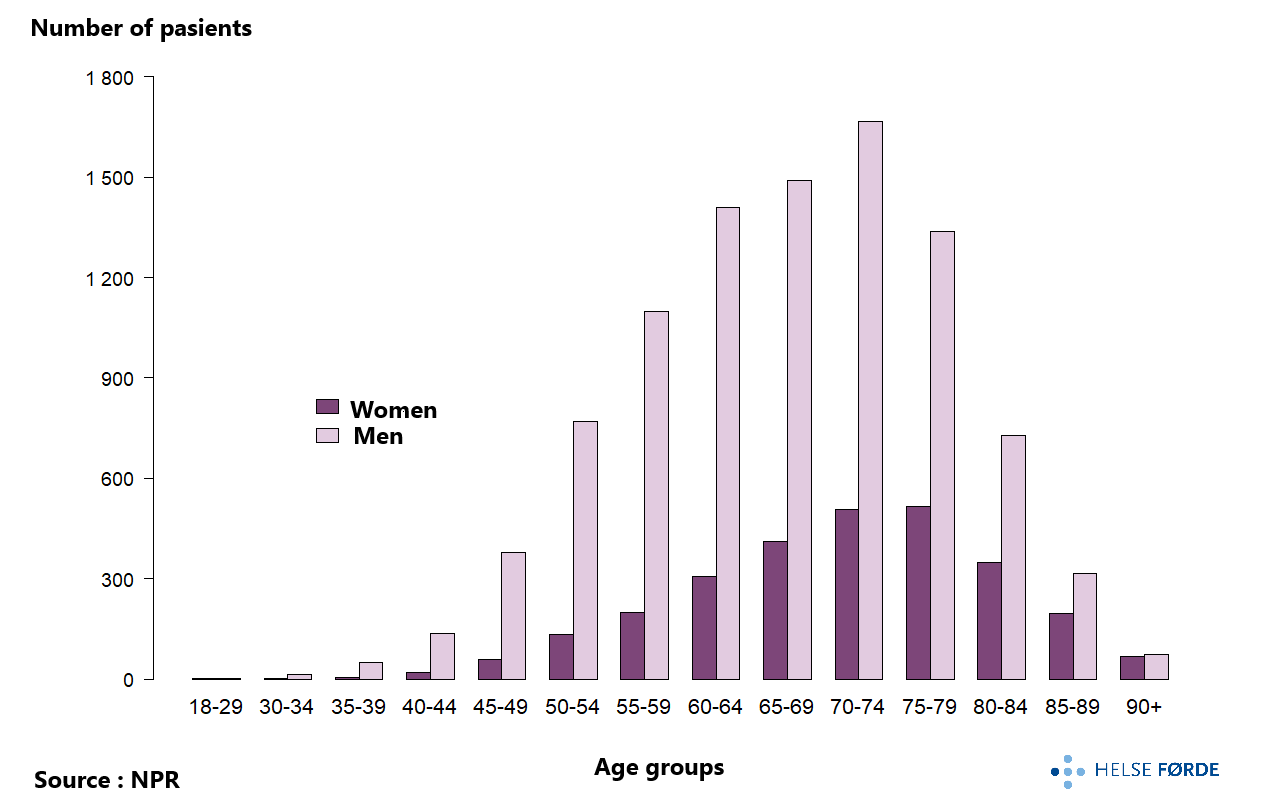

Just under 11,900 patients were admitted with acute myocardial infarction per year in 2018-2022. Two out of three patients were men, and the men were on average younger than the women (median age 70 and 78 years, respectively).

The average annual rate for Norway was 2.8 admissions with myocardial infarction per 1,000 population. The rate decreased during the period 2018-2022, with the largest reduction in the pandemic year 2020. The decline observed over many years likely reflects a real decrease in the number of people affected by myocardial infarction (see Annual Report 2021 Norwegian Myocardial infarction Register).

There was an urban-rural gradient in the rates; the lowest rate was in areas with the largest cities. The Finnmark hospital referral area had the highest prevalence, while the Sørlandet and Diakonhjemmet hospital referral area had the lowest prevalence of acute heart attack, using patients admitted for acute myocardial infarction as an indicator of coronary morbidity.

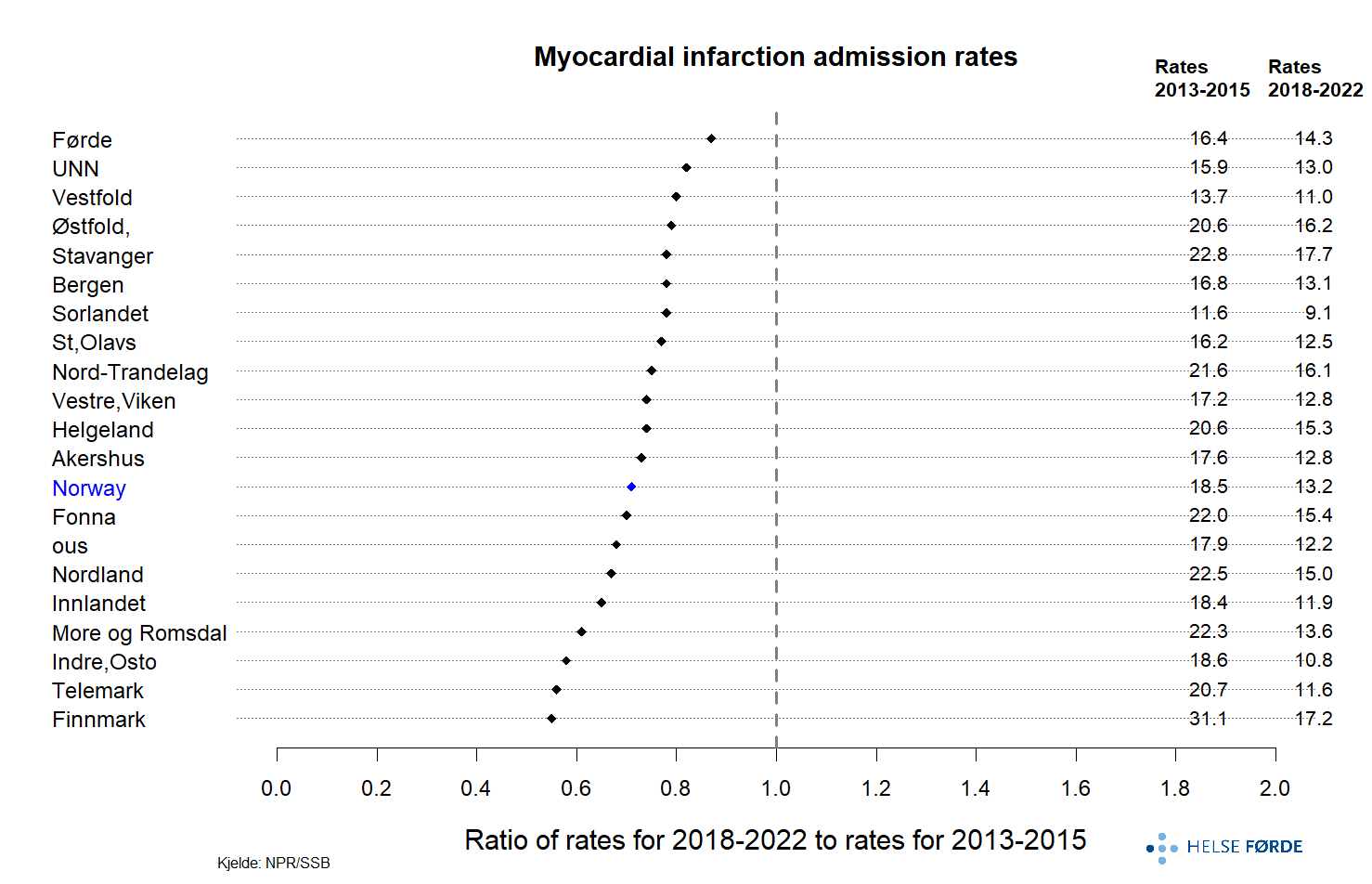

Just over 5,200 patients, 75 years and older, were admitted with acute myocardial infarction per year in 2018-2022. There was a clear reduction in the number of elderly with acute myocardial infarction compared to 2013-2015 (6,652 patients, Elderly Health Atlas), despite an increasing number of elderly (from 359,928 elderly on average per year in 2013-2015 to 409,950 in 2018-2022). The clear reduction in acute myocardial infarction in the elderly is also shown in the Myocardial infarction Register’s annual report for 2021.

The geographical variation in 2018-2022 was moderate. As in previous analyses (Elderly Health Atlas), the Finnmark hospital referral area had the highest and the Sørlandet hospital referral area had the lowest rates. The average annual rate for Norway was 12.8 admissions for the elderly with myocardial infarction per 1,000 population. The annual rates clearly decreased in most hospital referral areas in 2018-2022.

For all hospital referral areas, there was a decrease in the rate of admission for acute myocardial infarction for the elderly, with the largest changes seen in the hospital referral areas of Finnmark, Telemark, and Inner Oslo. The change in rate is illustrated by calculating the ratio between the average annual rate for the periods 2018-2022 and 2013-2015.

In other words, there was a reduction in the number of myocardial infarction patients during a period when the

number of elderly increased (from 359,928 elderly on average per year in 2013-2015 to 409,950 in 2018-2022).

Revascularization

- The geographical variation in revascularization rates was moderate when looking at the elderly (75 years and older) in isolation, and small for the general population.

- The admission rate for myocardial infarction did not correlate with the revascularization rate for the elderly (75 years and older). For all adults combined (18 years and older), the correlation was moderate.

- The majority (77%) of patients who were revascularized were men.

The main goal of acute treatment for myocardial infarction is to limit damage to the heart muscle by opening up blood vessels; revascularization. Depending on the distance to the hospital and the type of infarction, it is recommended that patients receive thrombolytic treatment (clot-dissolving treatment), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI, angioplasty), or bypass surgery.

X-ray examination of the coronary arteries in the heart with the injection of contrast fluid, and possible mechanical angioplasty, is performed at ten hospitals in Norway. Patients can be directly admitted to such an “invasive hospital” or transferred from other hospitals. Heart surgery is also performed at five of the hospitals (Annual Report 2021 Norwegian Myocardial infarction Register).

As in the Elderly Health Atlas, acute treatment with thrombolysis is not included in the analyses, and revascularization is not limited to patients with myocardial infarction.

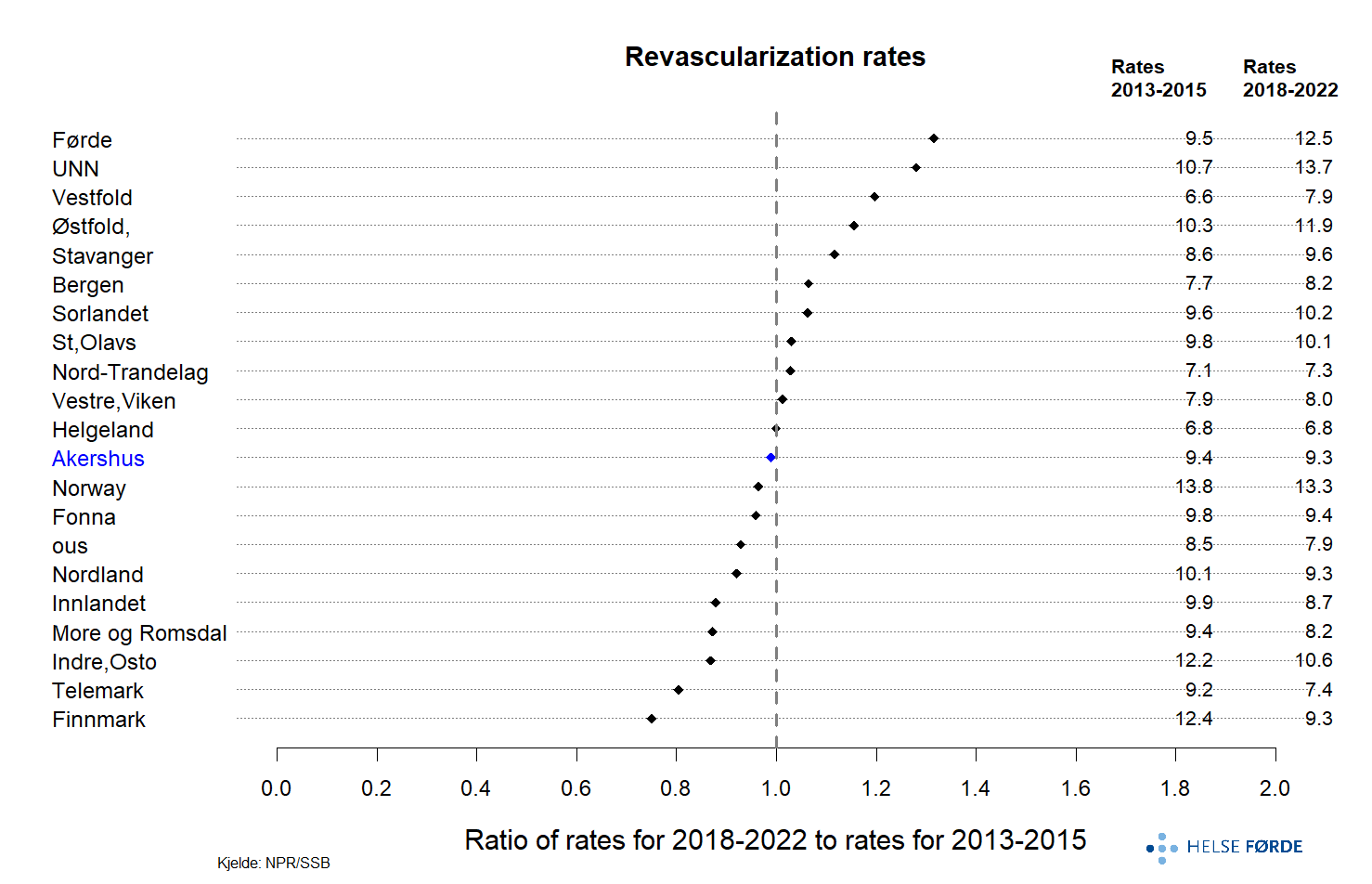

A total of 13,038 revascularizations were performed, distributed among 12,252 patients on average per year during 2018–2022, in the age group of 18 years and older. The number includes all patients, not only those with myocardial infarction. The majority were men (77%) who underwent heart revascularization. The rate of revascularization was 3.1 per 1,000 population for Norway.

The hospital referral areas areas in Northern Norway had the highest rate of revascularization, and the Diakonhjemmet area had the clearly lowest rate. Finnmark had the highest rate of revascularization was expected since they also had the highest rate of heart attacks. There is a positive moderate correlation between the rates of admission and revascularization (r=0.57), and the correlation is statistically significant (p=0.006) for the age group 18 years and older. A positive correlation was expected because revascularization is a treatment for, among other things, heart attacks. Catchment areas with a high prevalence of infarction should have a high revascularization rate.

The geographical variation was small when excluding the highest and lowest rates for revascularization (FT2=1.6 and SCV2=1.9).

On average, 3,787 revascularizations were performed for the elderly (75 years and older) per year in 2018-2022, distributed among 3,584 patients, and 69% of the patients were men. The number of revascularizations per year was roughly unchanged from 2013-2015 (3,403, Elderly Health Atlas) despite a clear reduction in the number of heart attacks. The revascularization rate was 9.3 per 1,000 population per year for the elderly in Norway (2018-2022).

The revascularization rates were highest for the elderly from the hospital referral areas in Northern Norway. The geographical variation can be characterized as moderate (FT2=1.8 and SCV=3.8), with the highest rate for the elderly in the UNN referral area and the lowest in Inner Oslo. The rate increased significantly in the Finnmark hospital referral area from 2019, while there was a decline in 2013-2015 (Elderly Health Atlas).

In some parts of the country, the rates for both admission and revascularization were high – for example, in Finnmark. In other parts of the country, there was a high prevalence of heart attacks and a low revascularization rate – for example, in Nord-Trøndelag. The correlation between the rates of admission with myocardial infarction and revascularization was small and not statistically significant (r=0.27, p=0.2) – the same was seen for 2013-2015 (Elderly Health Atlas).

The lack of correlation between admission and revascularization rates, and the lower use of revascularization for the elderly in many hospital referral areas, may be due to different practices, service offerings, and priorities. We do not know whether the degree of morbidity among myocardial infarction patients varied more among the elderly than in the overall adult group (18 years and older) where the correlation was moderate.

There was no clear change in the use of heart revascularization for the elderly in Norway from 2013-2015 to 2018-2022. The change is illustrated by calculating the ratio between the average annual revascularization rate for the periods 2018-2022 and 2013-2015 (see Elderly Health Atlas). However, in the hospital referral areas of Nordland and UNN, the rate increased, while in the Telemark area, it decreased.

Rehabilitation

- In the period 2018-2022, only 14% of patients received standard rehabilitation after an acute myocardial infarction in Norway, despite well-documented effects of cardiac rehabilitation.

- 26% of patients received standard rehabilitation, learning and mastery courses (LMC), or training in specialist health services after an acute heart attack.

- There was significant geographical variation in the use of rehabilitation after myocardial infarction, even when LMC and training in specialist health services were included in the analyses.

- Few elderly patients received rehabilitation after myocardial infarction.

- Content, organization, and start time varied geographically.

Rehabilitation has a clear secondary preventive effect on heart attacks, significantly impacting both individuals and society. Rehabilitation as part of secondary preventive treatment is recommended for all patients after a heart attack. Rehabilitation is cost-effective, improves quality of life, reduces the risk of recurrence, death, and rehospitalization. Research in the field is of the highest quality (class 1A) and provides clear recommendations (Visseren et al. 2021, Ambrosetti et al. 2020).

About This Healthcare Atlas

The Healthcare Atlas examines the cardiac rehabilitation that the patient received in the period from discharge from the hospital after an acute myocardial infarction and six months forward.

Activity in specialist health services coded as rehabilitation with the codes

- Z50.0 Rehabilitation after heart disease,

- Z50.80 Complex rehabilitation,

- Z50.89 Simple rehabilitation, and

- Z50.9 Treatment involving the use of unspecified rehabilitation measures is called “standard rehabilitation” in this health atlas.The use of these codes should indicate that the activity is targeted, planned, and interdisciplinary. See more about code quality under the discussion of the method.

To get a broader picture of the services offered to patients in the first six months after the infarction, we supplemented analyses of standard rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction with participation in Learning and Mastery Courses (LMS courses) and training in specialist health services, and training with a physiotherapist with municipal operating grants / who has billed Helfo. That the health services for patients vary geographically in terms of content, duration, and organization is also evident from feedback from the field.

Based on the Myocardial infarction Register’s definition of cardiac rehabilitation; “education on how to reduce the risk of a new myocardial infarction and the offer of physical training” (Annual Report 2022), we understand that participation in LMS courses and training is part of cardiac rehabilitation, and including LMS courses and training for more pragmatic reasons seems natural. To what extent such services meet the conditions for achieving rehabilitation results, which are the basis for the guidelines (Visseren et al. 2021), is not available through the data we have.

The analysis results of cardiac rehabilitation will be influenced by how we understand the concept of rehabilitation, what data and methods we have used in the analyses, and the quality of the registered data.

Definitions and Operationalization of the Concept of Rehabilitation

The definition of rehabilitation can vary in different contexts. Here we briefly mention the understanding of cardiac rehabilitation that this health atlas is based on:

“The sum of activities and interventions necessary to ensure physical, mental, and social conditions so that patients with chronic or post-acute heart disease can return to their previous place in society and live an active life” (Helsebiblioteket).

Further on the content of rehabilitation: “Cardiac rehabilitation consists of complex, long-term programs involving medical evaluation, prescription of physical activity, reduction of risk factors, education, and psychosocial support. The programs are carried out by a multidisciplinary team with a minimum of 4 different professional groups for simple rehabilitation and a minimum of 6 different professional groups for complex rehabilitation” (Helsebiblioteket).

The European guidelines, which are supported in Norway, recommend that multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation should include exercise, education, follow-up, and management of lifestyle and risk factors, as well as psychosocial support (Visseren et al. 2021).

The analyses of standard rehabilitation in the health atlas are based on data from the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR). The regulations for activity-based funding (ISF regulations 2022, chapter 6.12) set requirements for the use of rehabilitation codes, including the number of professional groups that must be involved. The concept of rehabilitation is thus operationalized through activity-based funding (ISF), while funding is linked to rehabilitation activities that meet the requirements and are correctly coded.

Quality of Rehabilitation Coding

The main data source for the analyses of rehabilitation in the health atlas is the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR), a national health register containing information about all patients who have received rehabilitation in specialist health services in Norway, both public health services and private ones with agreements with the public sector. NPR is primarily developed for administrative purposes. In the health atlas, the information is used to assess whether there is geographical variation in rehabilitation in the six months after patients were acutely admitted with a heart attack.

A challenge related to the analysis of this type of data is whether the coding quality is good enough. Errors or omissions in coding will result in inaccuracies in describing rehabilitation in specialist health services. Much has been done to improve and harmonize coding practices, but we cannot rule out that there are some errors or omissions in our dataset, meaning the data may not fully reflect the actual activities performed.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health comments on the quality of rehabilitation coding in general in the report “Rehabilitation in Specialist Health Services 2017-2021”. They mention that there may be underreporting of outpatient and day rehabilitation but have not investigated the extent of this or how it manifests. Stays have previously been incorrectly registered as inpatient stays instead of a series of outpatient contacts in some health trusts (Annual Reports from 2019 and 2021, Settlement Committee).

The Norwegian Directorate of Health also mentions in the report that in recent years more private providers have reported to NPR, but there is still uncertainty in the coding. Analyses of day and outpatient activities related to private rehabilitation institutions should therefore be interpreted with caution.

To minimize the challenge of coding errors, including the procedure codes and tariff codes we have used, we have spent time preparing and quality-checking the datasets from NPR and KPR, familiarizing ourselves with the coding rules, and talking to professionals about the coding of activities. We have assessed that the results contain as few errors as possible based on the available data.

Cohort Analysis

In the Health Atlas for Heart Attack, we used cohort analysis where we followed patients with acute myocardial infarction from discharge after the myocardial infarction for the first six months forward, examining participation in rehabilitation during this period.

We used a narrower definition of patients with myocardial infarction in the analyses related to rehabilitation (I21 acute myocardial infarction as the main condition) than in the analysis of admissions with myocardial infarction(I21 acute heart attack, or I22 subsequent heart attack, as the main or secondary condition). The analyses of admissions with myocardial infarction are an update of analyses in the Elderly Health Atlas, and we have therefore used the same codes as in the Elderly Health Atlas. By using a strict definition in the analyses of rehabilitation after an acute heart attack, we are more confident that we include the correct patient group. We saw in the data from NPR that most of the rehabilitation occurred after inpatient stays with I21 (acute heart attack) as the main condition, and not after stays with I22 (subsequent heart attack), or where the codes were used as secondary conditions. The ICD-10 codes for acute myocardial infarction have been found to be of good quality (Varmdal et al. 2021).

We found that 75% of rehabilitation episodes were completed within the first six months. Extending the period would have resulted in slightly more episodes. On the other hand, a cohort analysis over a longer period would entail greater uncertainty regarding whether the rehabilitation was related to the myocardial infarction.

Need for Guidelines and Quality Indicators

The geographical variation in cardiac rehabilitation, based on our analyses and information from professionals from different parts of the country, appears to be supply-driven rather than need-driven. We find areas in Norway with a high prevalence of heart attacks, such as Finnmark, where the provision and use of cardiac rehabilitation are limited. We would characterize the geographical variation as undesirable, despite the caveat about coding quality. The analyses show an underuse of rehabilitation after heart attacks, and there is a need for measures to improve the service offering for patients after heart attacks.

To achieve a more equitable rehabilitation service regardless of where one lives, it seems there is a need for national guidelines for rehabilitation after heart attacks - and that effective rehabilitation services are established for patients across the country. The work on guidelines started in 2023. Specific quality indicators could also be measures to improve the extent and quality of services.

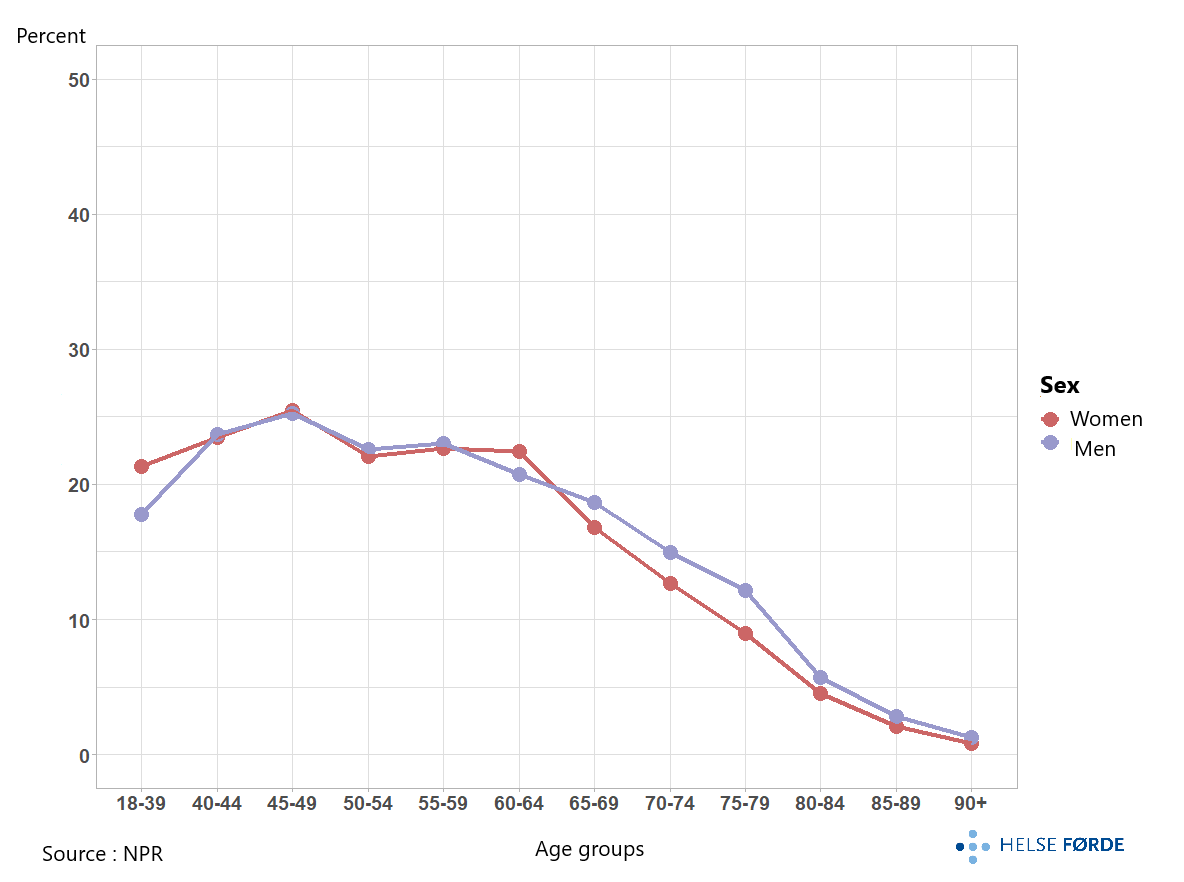

14% of patients received standard rehabilitation after myocardial infarction. This is a very low percentage - for both genders and all age groups ,compared to the guidelines that recommend rehabilitation for all with coronary heart disease (Visseren et al. 2021).

There was significant geographical variation in the percentage who received standard rehabilitation after myocardial infarction based on both the extermal qutient and the systematic component of variation excluding referral areas with highest and the lowest percetage of rehabilitation (EQ2=9.3 and SCV2=45). Extermal Qutient and systematic component of variation are used to support the assessment of geographical variation. Patients from the Vestfold hospital referral area had the highest likelihood of receiving standard rehabilitation, with 41% receiving such rehabilitation ,on average per year during 2018-2022. In nine of the hospital referral areas, 5% or fewer received standard rehabilitation after an myocardial infarction.

There were regional differences in the use of standard rehabilitation, with the lowest percentage participation in Northern Norway (4%) and the highest in Southeastern Norway (16%).

Within the hospital referral areas of the health trusts in the same health region, the use of standard rehabilitation also varied. In Southeastern Norway, the Vestfold hospital referral area had the highest percentage of myocardial infarct patients receiving such rehabilitation, while the Østfold and Telemark catchment areas had the lowest in the country. Similarly, within Western Norway; high participation rates in the Bergen area, and low in the Stavanger area. In Central Norway, the percentage was systematically highest for patients from the Møre og Romsdal catchment area.

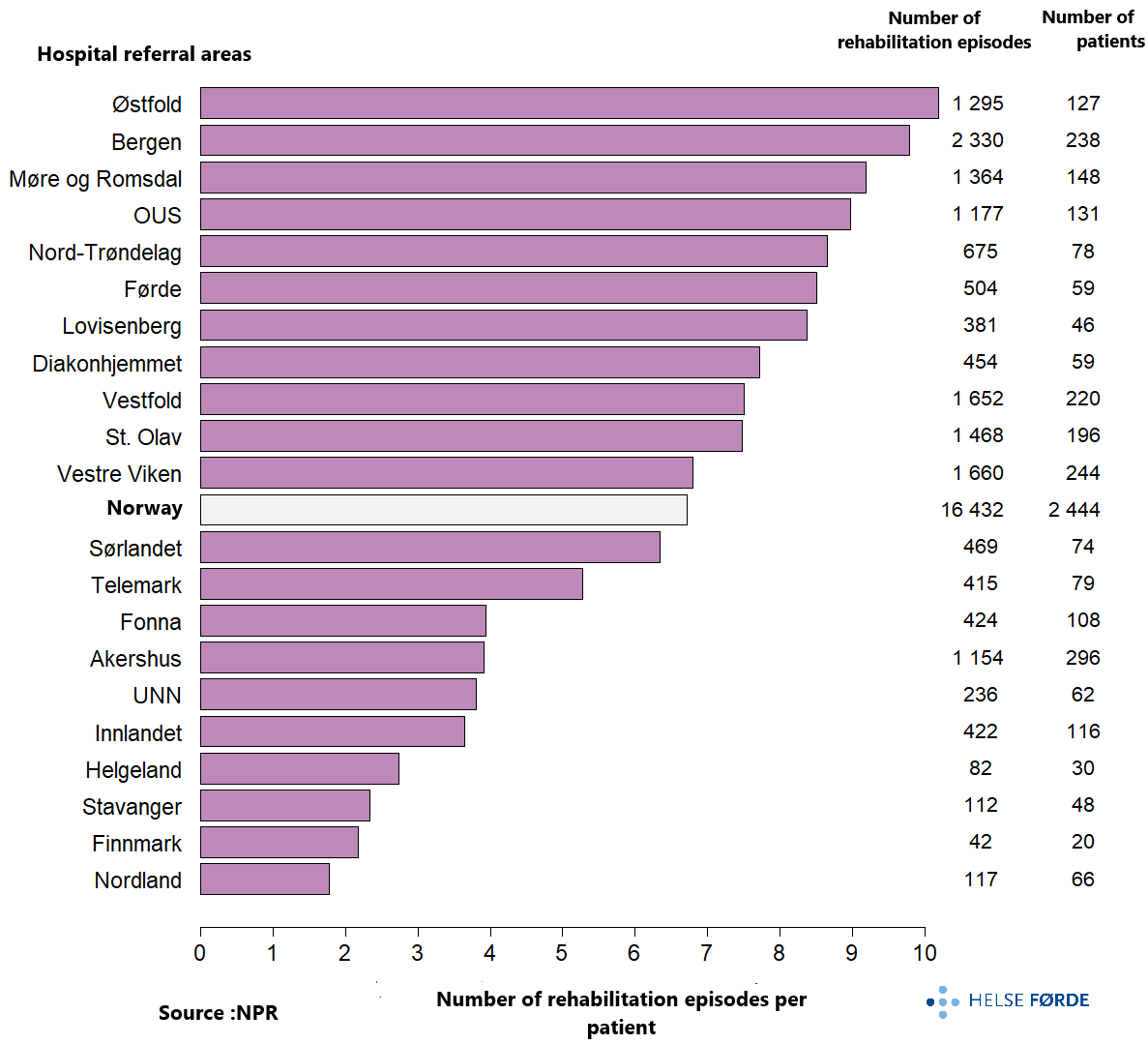

The extent of the use of standard rehabilitation varied greatly. In the OUS catchment area, an average of 15 episodes per patient was registered, and for Norway, 6.5 episodes per patient for those who received standard rehabilitation. In some catchment areas, very few rehabilitation episodes per patient were registered, which could indicate a limited service offering but also raise suspicion of inadequate coding of standard rehabilitation after an acute heart attack. The report “Rehabilitation in Specialist Health Services 2017-2021” also mentions that there may be underreporting of diagnosis codes for rehabilitation (z-codes) in day and outpatient clinics in hospitals.

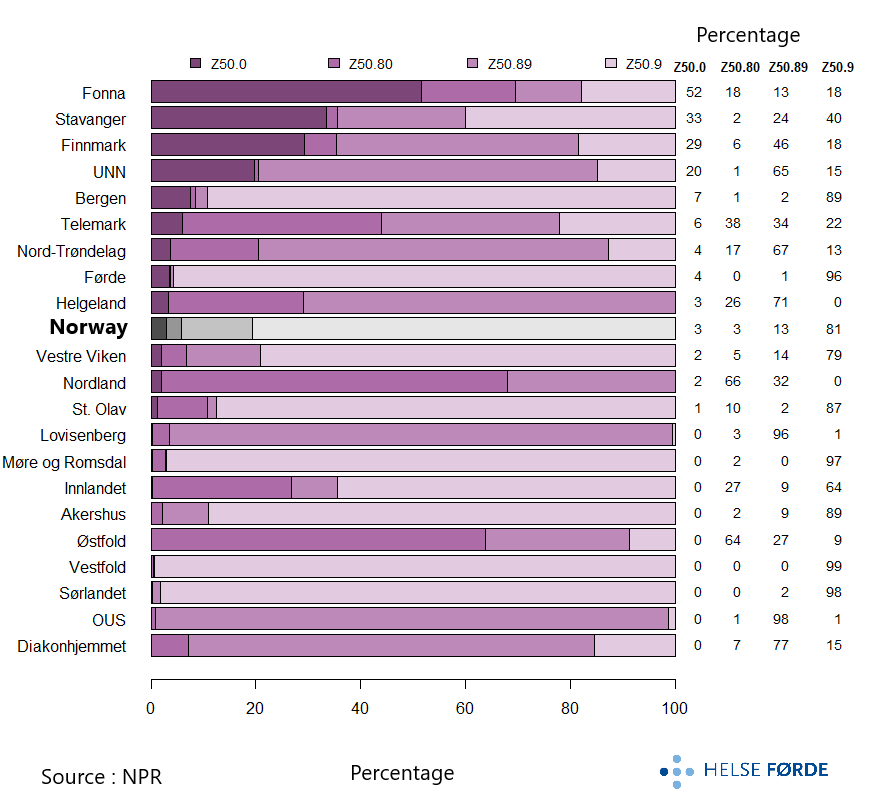

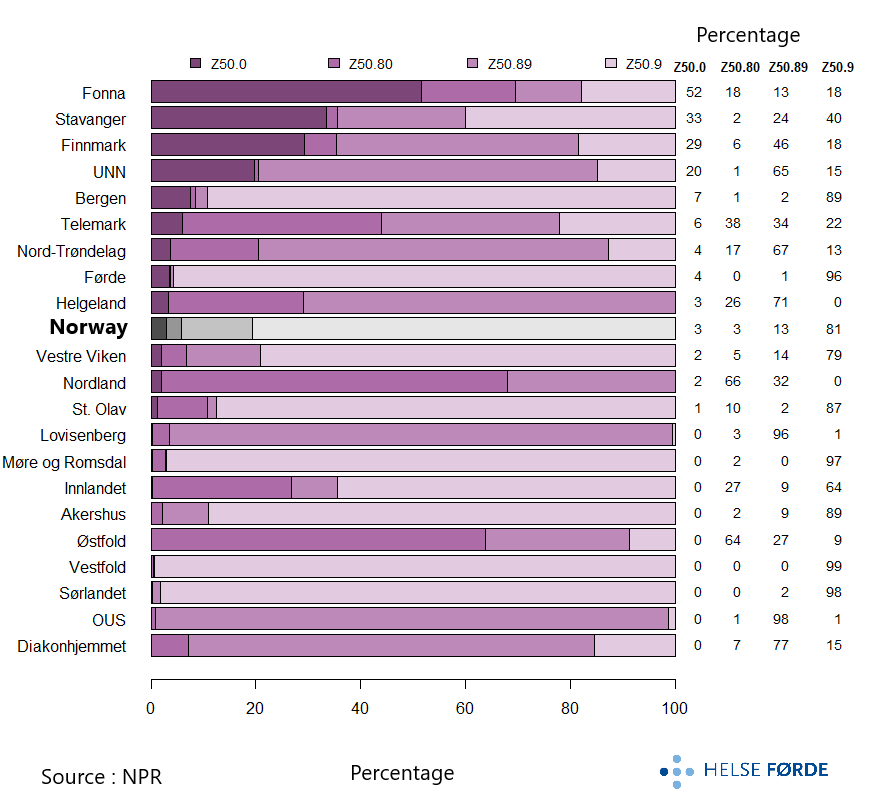

There were differences in the type of standard rehabilitation, based on how the activities were coded. For Norway as a whole, most of the activity was outpatient rehabilitation, registered with Z50.9. That cardiac rehabilitation mainly occurs on an outpatient basis corresponds with professionals’ descriptions of the field.

The code for rehabilitation after heart disease, Z50.0, was rarely used, with a few exceptions (Fonna, Stavanger, Finnmark, and UNN areas). The reason for this has not been investigated. That the analyses in the health atlas are based on a broader set of codes than just Z50.0 seems essential when highlighting cardiac rehabilitation.

In several areas with a low percentage of standard rehabilitation after an acute heart attack, including the Helgeland and Østfold catchment areas, much of the activity occurred as inpatient stays, coded with Z50.80 (complex rehabilitation) and Z50.89 (simple rehabilitation).

There were more episodes coded with Z50.80 or Z50.89 in Northern Norway than in other regions. This finding indicates relatively greater use of inpatient stays in the region, which seems likely due to long travel distances for participation in outpatient or day rehabilitation.

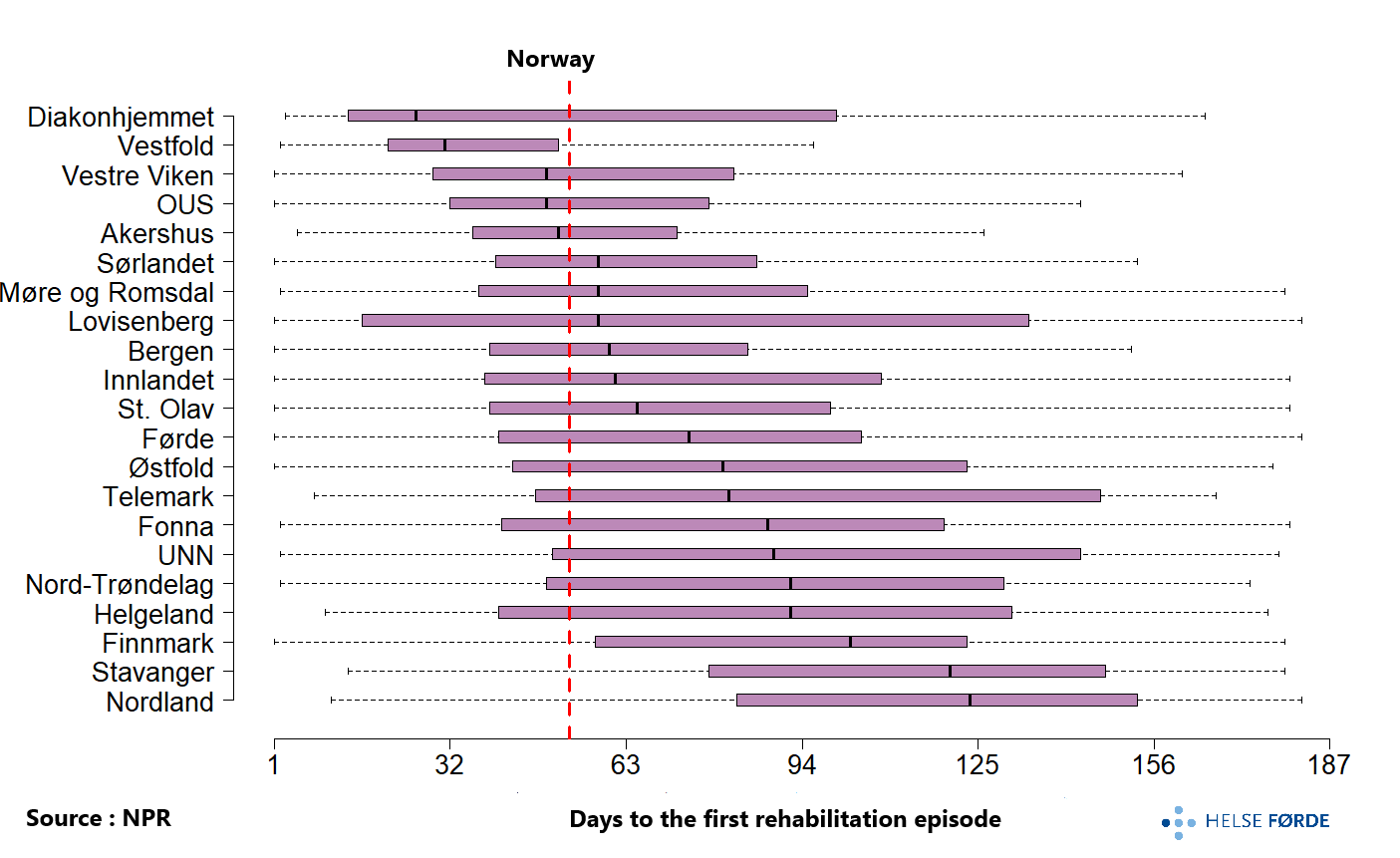

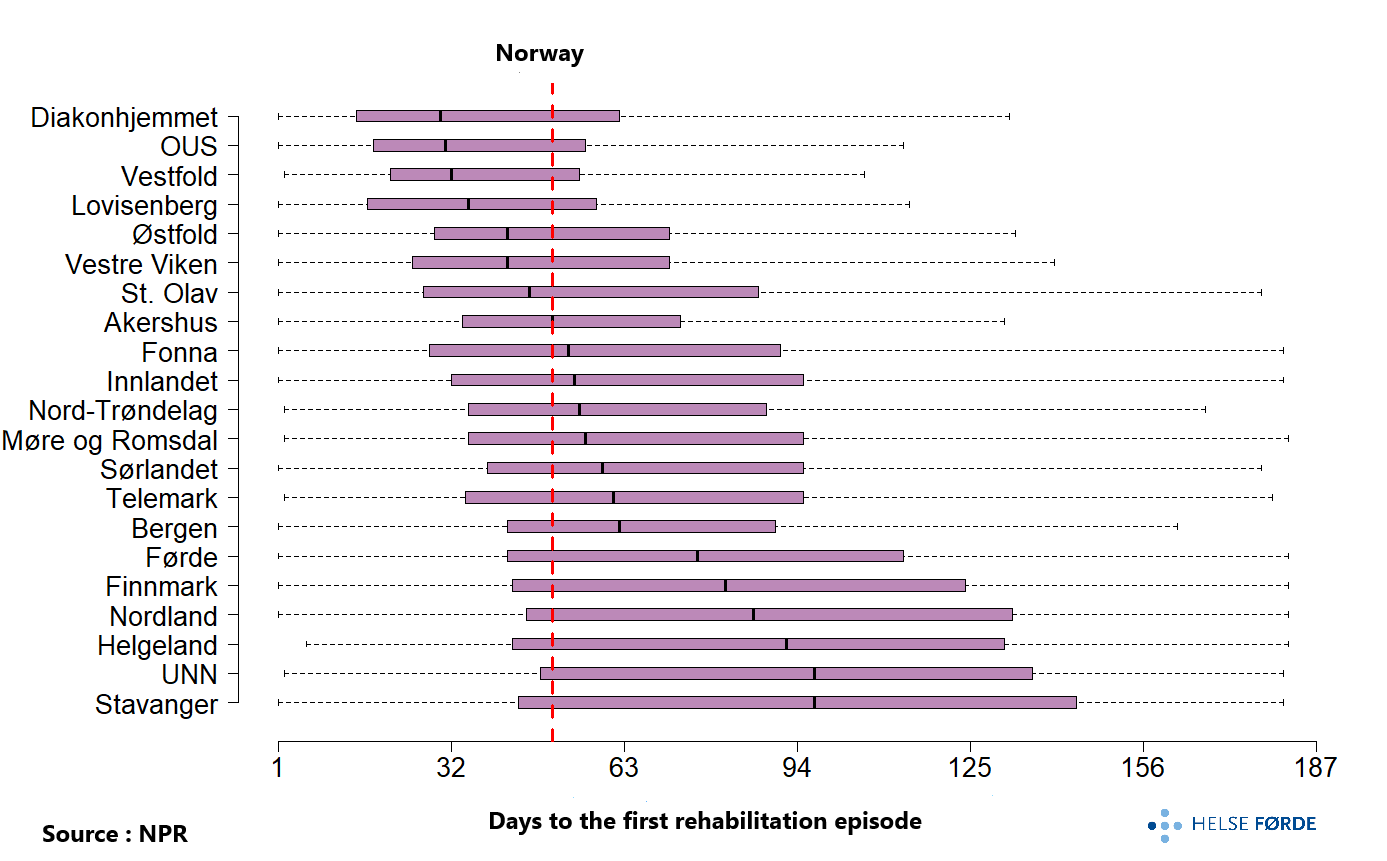

The number of days before the start of standard rehabilitation after an acute myocardial infarction also varied. There was a tendency for earlier start with standard rehabilitation in central areas of Eastern Norway and later start after a myocardial infarction in the north of the country. About half of the patients from the Diakonhjemmet (Oslo West) and Vestfold hospital referral areas started standard rehabilitation one month after discharge from the acute stay, while in the Stavanger and Nordland areas, about half started only after four months. For Norway (red line), half of the patients had started standard rehabilitation after 53 days.

The analyses concerning standard rehabilitation are based on codes for rehabilitation (z-codes). There are explicit requirements for a service to be called rehabilitation and to use such a rehabilitation code. Among other things, a plan must be developed for each patient, and several professional groups must be involved (see ISF regulations 2022). Although some of the explanation for the low use of standard rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction may be due to underreporting of z-diagnosis codes, it still seems that standard rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction is a limited service offering in Norway. The impression of a limited service offering for standard cardiac rehabilitation in Norway is also supported by contact with professionals.

The number of days before the start of standard rehabilitation after an acute myocardial infarction also varied. There was a tendency for earlier start with standard rehabilitation in central areas of Eastern Norway and later start after a myocardial infarction in the north of the country. About half of the patients from the Diakonhjemmet (Oslo West) and Vestfold hospital referral areas started standard rehabilitation one month after discharge from the acute stay, while in the Stavanger and Nordland areas, about half started only after four months. For Norway (red line), half of the patients had started standard rehabilitation after 53 days.

The analyses concerning standard rehabilitation are based on codes for rehabilitation (z-codes). There are explicit requirements for a service to be called rehabilitation and to use such a rehabilitation code. Among other things, a plan must be developed for each patient, and several professional groups must be involved (see ISF regulations 2022). Although some of the explanation for the low use of standard rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction may be due to underreporting of z-diagnosis codes, it still seems that standard rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction is a limited service offering in Norway. The impression of a limited service offering for standard cardiac rehabilitation in Norway is also supported by contact with professionals.

68% of patients with acute myocardial infarction were men. The average age for men was 68 years and for women 74 years.

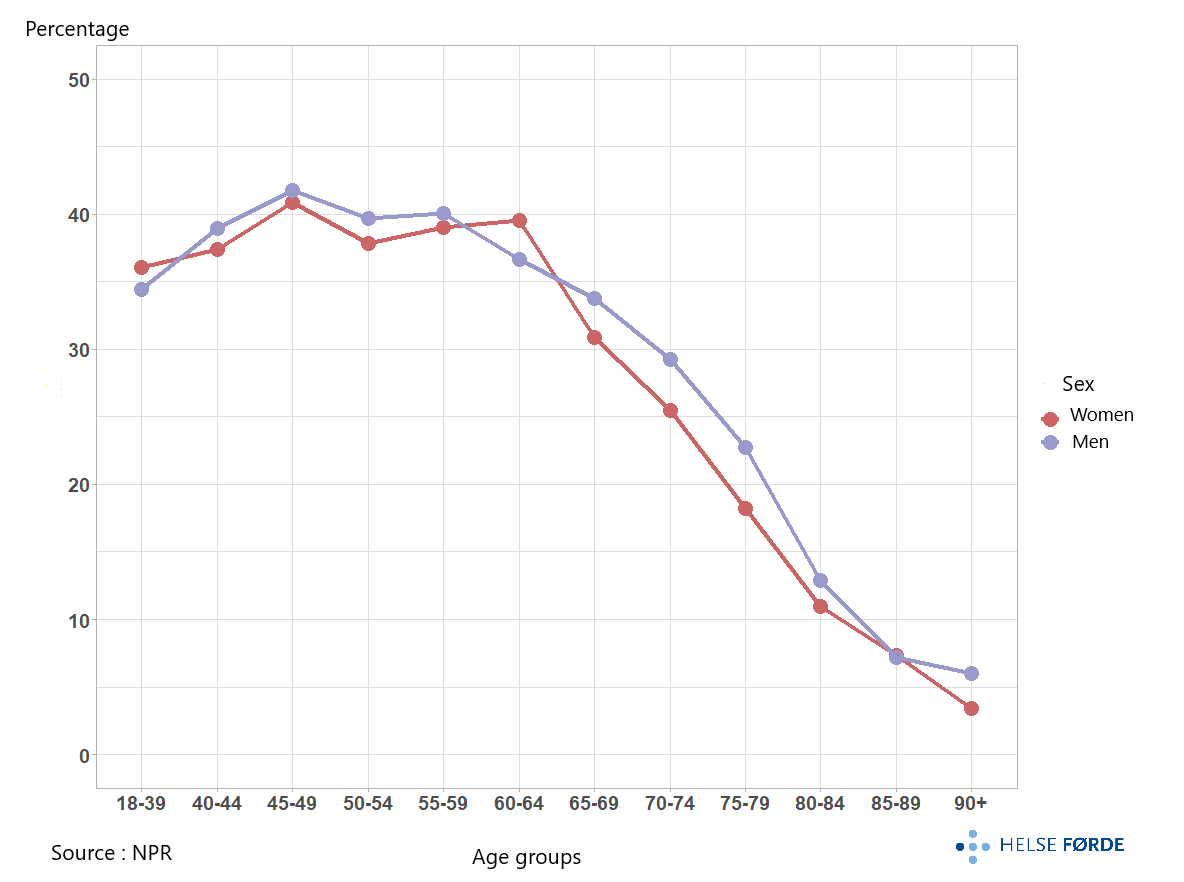

26% of patients received rehabilitation after an acute myocardial infarction if we included both standard rehabilitation, participation in learning and mastery courses (LMC), and training in specialist health services in the analyses. In the pandemic year 2020, the percentage was lowest. In only a few catchment areas was rehabilitation back to a “pre-pandemic level” in 2021. The low level of cardiac rehabilitation in 2020 was mainly due to the shutdown associated with the pandemic (Norwegian Directorate of Health 2022).

Participation in rehabilitation varied from 9% to 46% between the catchment areas of the health trusts, and few patients from Finnmark received rehabilitation, despite a high prevalence of myocardial infarction. The highest percentage was in the hospital referral areas with in the largest cities. The geographical variation can be characterized as systematic and large (FT2=4.5 and SCV2=23.4).

A similar extent of participation in rehabilitation was also revealed in a study of cardiac rehabilitation after first-time PCI (Olsen et al. 2018). Of those who participated in the study (82% of all with first-time PCI in 2008-2011), 28% had participated in cardiac rehabilitation. The study found similar trends to our analyses, also in geographical variation with the lowest participation in cardiac rehabilitation in Northern Norway and the highest in Southeastern Norway. Although both the patient sample, follow-up time (3 years versus our 6 months), and use of different methods (they questionnaires, we data from NPR), their results strengthen our findings of low participation and large geographical variation in cardiac rehabilitation in Norway.

The highest percentage of patients who received rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction was found in the hospital referral areas of OUS, Vestfold, and Diakonhjemmet. While the Vestfold area had a relatively large percentage receiving standard rehabilitation, the two areas in Oslo had little standard rehabilitation registered, but a relatively larger proportion participating in LMC courses and training.

For patients aged 65 and older, there was a clear reduction in the percentage of patients receiving standard rehabilitation, LMC courses, and/or training after a heart attack. That myocardial infarct patients in Norway who receive rehabilitation are relatively young has also been shown previously (Olsen et al. 2018). This contrasts with recommendations for rehabilitation at all ages (Ambrosetti et al. 2020). That older people are more likely to have more complex problems and different risk profiles than younger people is an argument for specialist health services to take responsibility for rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction also for the elderly.

The percentage of women (20%) who received rehabilitation was lower than for men (30%). This is also known from other analyses (Visseren et al. 2021). The fact that the women in our analyses were somewhat older than the men, and that the elderly are less likely to receive rehabilitation, may be one of the explanations for this finding.

For patients who received rehabilitation, the number of rehabilitation episodes they received in the first six months after an acute myocardial infarction varied geographically. For patients from the hospital referral areas of Bergen and Østfold, patients received an average of 10 rehabilitation episodes, and for Norway, the average was 7. Included in these analyses are episodes of standard rehabilitation, LMC courses, and/or training in specialist health services.

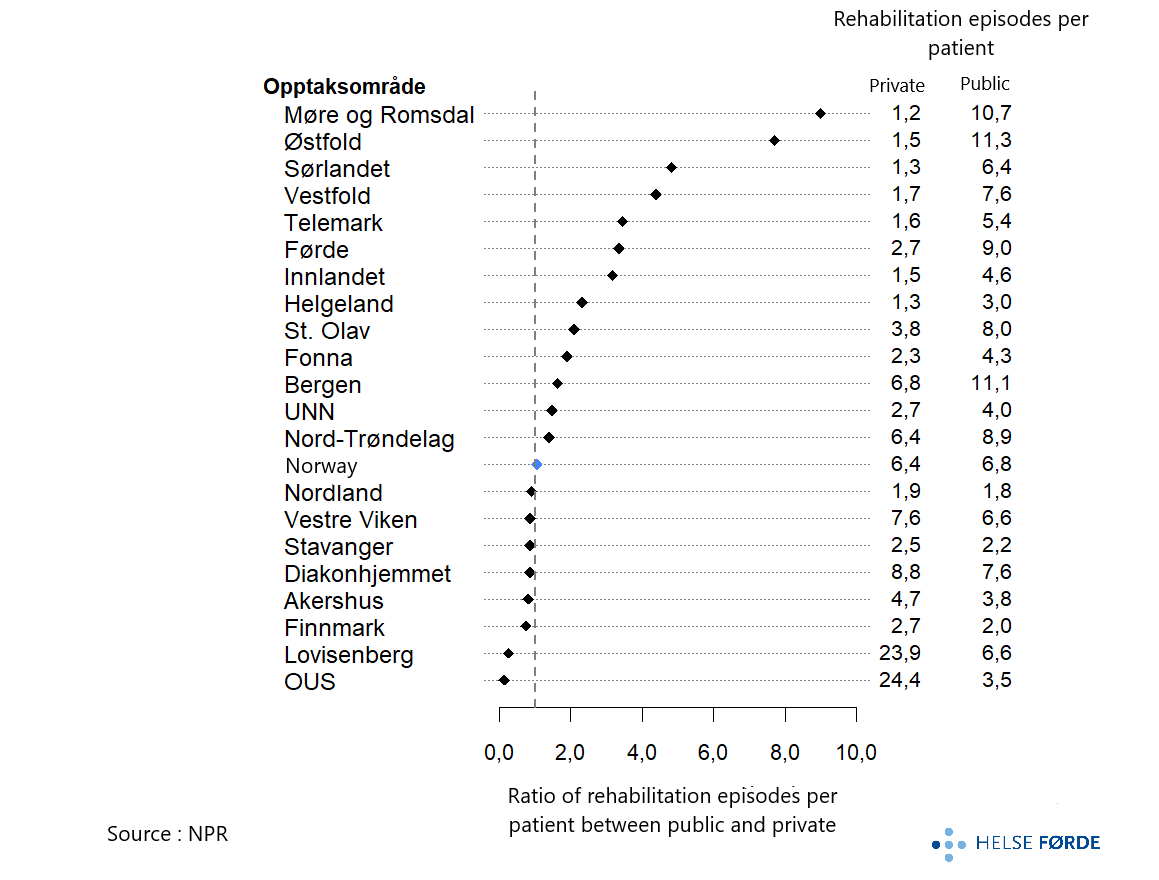

Most of the rehabilitation occurred in the public sector, and for Norway as a whole, 86% of rehabilitation episodes took place there. The highest percentage of private rehabilitation was in Oslo with 71% in the OUS hospital referral area, followed by 42% in the Stavanger area.

In most catchment areas, the number of rehabilitation episodes per patient was highest in the public sector. However, there were some contrasts in the country with 7 times more episodes per patient in the private sector than in the public sector in the OUS hospital referral area, and conversely, 9 times more episodes per patient in the public sector in the Møre og Romsdal hospital referral area. By private, we mean private institutions with agreements with the regional health authority.

The percentage distribution of types of rehabilitation measures after a heart attack; standard rehabilitation, education, and/or training, varied between different parts of the country based on the coding of activities. For Norway as a whole, only 60% of the episodes were coded as standard rehabilitation (coded with Z-codes), varying from 5% to 96% between catchment areas, and education in LMS courses accounted for 10%.

Physical training was a central part of rehabilitation after an acute heart attack. Training was either registered as individual episodes (31% of the episodes were only training), included as part of the LMS course, or included in the standard rehabilitation episode. Although training is a core component, the guidelines are clear that the effect of a cardiac rehabilitation program depends on participation in the entire interdisciplinary program, not just the physical training (Dibben et al. 2023 and Visseren et al. 2021).

In some catchment areas, standard rehabilitation was mainly coded as inpatient stays (Helgeland and Østfold). Otherwise, there appeared to be little rehabilitation after a heart attack. When we included LMS courses and training in the analyses, we found that patients still had a service offering after a heart attack.

That both the type of measures and the extent of the service offering varied geographically corresponds with results from previous studies of rehabilitation and secondary preventive measures in hospitals (Peersen et al. 2017, Peersen et al. 2021, and Olsen et al. 2018).

The number of days to the start of rehabilitation (standard rehabilitation, LMS courses, and/or training) varied greatly between hospital referral areas. The difference was nevertheless somewhat smaller than for standard rehabilitation alone. Half of the patients in several hospital referral areas in Oslo and around the Oslofjord started rehabilitation about one month after discharge from the acute stay. In the hospital referral areas in Northern Norway and Stavanger, rehabilitation started about three months after a myocardial infarction. For Norway (red line), half of the patients had started rehabilitation only after 50 days. This is despite the guidelines recommending starting as soon as possible after the myocardial infarction (Visseren et al. 2021).

There may be several explanations for the low participation in rehabilitation after a heart attack. It is beyond the scope of the health atlas to investigate this, but we will briefly mention some points. Referral routines, availability, travel distances, capacity, how well the service is developed, patient preferences, knowledge of existing services, and knowledge of patients needing rehabilitation may vary, as we understand from contact with professionals and as highlighted in research articles ( Peersen et al. 2021, Olsen et al. 2018, and Piepoli et al. 2016).

In the latest annual report, the Myocardial infarction Register (2022) highlights that only half of those who responded to questions from the register reported that they had been referred to cardiac rehabilitation, defined as “education on how to reduce the risk of a new myocardial infarction and the offer of physical training.” There were also large regional differences in referrals, from 37% in Western Norway to 64% in Southeastern Norway, which may affect the participation rate in cardiac rehabilitation. The guidelines recommend finding methods to increase referral and participation in cardiac rehabilitation, so that as many as possible can benefit from services that have a clear health and societal benefit (Visseren et al. 2021).

Training with Physiotherapists in Municipalities

Four percent of patients trained with physiotherapists in the municipalities in the first six months after an acute myocardial infarction in 2018-2021. There was significant geographical variation in training with physiotherapists.

Four percent of patients trained with physiotherapists in the municipalities in the first six months after an acute myocardial infarction in 2018-2021, based on information from physiotherapists who submitted invoices to Helfo.

There was significant geographical variation in the percentage of patients who trained with physiotherapists in the municipalities after an acute myocardial infarction in 2018-2021. The percentage varied from 13% in the Stavanger catchment area to 2% in Inner Oslo.

In the Stavanger hospital referral area, there is a well-established collaboration between specialist health services and municipal physiotherapists in cardiac training. In this catchment area, the use of standard rehabilitation, learning and mastery courses, and training in specialist health services was very low.

Other hospital referral areas with little use of rehabilitation in specialist health services, such as Finnmark and Helgeland, also had little use of training with physiotherapists in the municipalities after myocardial infarction.

We are nevertheless not aware of the total service offering patients received in the municipalities; this only includes training with physiotherapists who submitted invoices to Helfo. Information about training with salaried physiotherapists in the municipalities who do not submit invoices to Helfo, training or other services at health and wellness centers, or in municipal institutions, is currently not available in the datasets from KPR on which these analyses are based. The analyses are based on small numbers and may be influenced by chance.

About the Atlas

The Health Atlas for Myocardial infarction is based on information provided by the Norwegian Directorate of Health from the Norwegian Patient Register (NPR) and the Municipal Patient and User Register (KPR) for the period 2018 to 2022.

From KPR, information about training with physiotherapists for patients after an acute myocardial infarction has been collected. Other analyses are based on information from NPR.

Population numbers are obtained from Statistics Norway (SSB).

Disclaimer

Helse Førde is solely responsible for the interpretation and presentation of the data provided. NPR and KPR are not responsible for analyses or interpretations based on the data they have provided.

The four regional health authorities have a statutory responsibility to provide specialist health services to the population, and the services should be equitable regardless of where one lives (Specialist Health Services Act). In assessing geographical variation in the population’s use of health services, the country is therefore divided according to the health authorities’ referral areas.

The analyses in the healthcare atlas are conducted based on the hospital referral area where the patient lives, not where they received treatment. The inhabitants of the different hospital referral areas have different age and gender compositions. The rates in the atlas are therefore age and sex adjusted to compare more homogeneous groups’ use of health services than without such adjustment. If information about the municipality where the patient lived was missing in the datasets, the patient was excluded from the analyses. Through the analyses, the regional health authorities can form a picture of how the healthcare responsibility for their referral area is being fulfilled.

Information about the division into catchment areas, population numbers, and median age of the inhabitants (2020) used in this atlas can be found below.

The list below shows which health trusts or hospitals have defined hospital referral areas and the short names used in the atlas. Which municipalities and districts belong to each referral area can be found here.

The referral areas of Diakonhjemmet Hospital and Lovisenberg Diaconal Hospital (i.e., districts in Oslo) are combined into one referral area; Inner Oslo, where results from 2018-2022 are compared with the Elderly Health Atlas (2013-2015), and in analyses concerning training with physiotherapists due to the small number of patients.

| Hospital referral area | Short name |

|---|---|

| Finnmarkssykehuset HF | Finnmark |

| Universitetssykehuset i Nord-Norge HF | UNN |

| Nordlandssykehuset HF | Nordland |

| Helgelandssykehuset HF | Helgeland |

| Helse Nord-Trøndelag HF | Nord-Trøndelag |

| St. Olavs hospital HF | St. Olav |

| Helse Møre og Romsdal HF | Møre og Romsdal |

| Helse Førde HF | Førde |

| Helse Bergen HF | Bergen |

| Helse Fonna HF | Fonna |

| Helse Stavanger HF | Stavanger |

| Sykehuset Østfold HF | Østfold |

| Akershus universitetssykehus HF | Akershus |

| Oslo universitetssykehus HF | OUS |

| Lovisenberg diakonale sykehus | Lovisenberg |

| Diakonhjemmet sykehus | Diakonhjemmet |

| Sykehuset Innlandet HF | Innlandet |

| Vestre Viken HF | Vestre Viken |

| Sykehuset i Vestfold HF | Vestfold |

| Sykehuset Telemark HF | Telemark |

| Sørlandet sykehus HF | Sørlandet |

The Health Atlas for Myocardial infarction is developed in collaboration with a resource group consisting of:

- Torstein Hole, Specialist in Internal Medicine and Cardiology, MD, Helse Møre og Romsdal, NTNU

- Charlotte B. Ingul, Specialist in Internal Medicine and Cardiology, MD, St. Olavs Hospital, NTNU, Nord University

- Tove Johansen, Analyst, SKDE

- John Munkhaugen, Specialist in Internal Medicine and Cardiology, MD, Drammen Hospital, UiO

- Tone Merete Norekvål, PhD, Research Group Leader, Cardiology Department, Haukeland University Hospital, Professor, University of Bergen and Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

- Barthold Vonen, Director, SKDE

During the project period, we have been in contact with professional environments and individuals in various parts of the country. This is to ensure that the analysis results can provide the best possible picture of practice.

Thank you for contributing to making the atlas practical and relevant.

The Healthcare Atlas is developed by Helse Førde HF by Marte Bale, Haji Kedir Bedane, Maria Holsen, Knut Ivar Osvoll, and Oddne Skrede.

Do you have questions?

For questions or comments, please contact the Health Atlas Service at Helse Førde HF through [helseatlas@helse-forde.no]